For over two decades, India believed it had lost one of its most elusive and enigmatic wild cats—the caracal. Seldom seen and often misunderstood, this sleek predator had seemingly vanished from the subcontinent’s grasslands and scrub forests.

But recent sightings in Rajasthan and now Madhya Pradesh are rewriting that narrative. Not only has the caracal survived, but it’s also beginning to make a powerful comeback.

The latest evidence comes from Gandhi Sagar Wildlife Sanctuary in Madhya Pradesh, where a camera trap captured a caracal three times in a single night—the first confirmed sighting in the state in over 20 years.

Also you can read, Tesla Inc. officially launched its operations in India with the opening of its first showroom in Mumbai, you can read more about Tesla India in our article.

Table of Contents

A Ghost of the Grasslands Returns

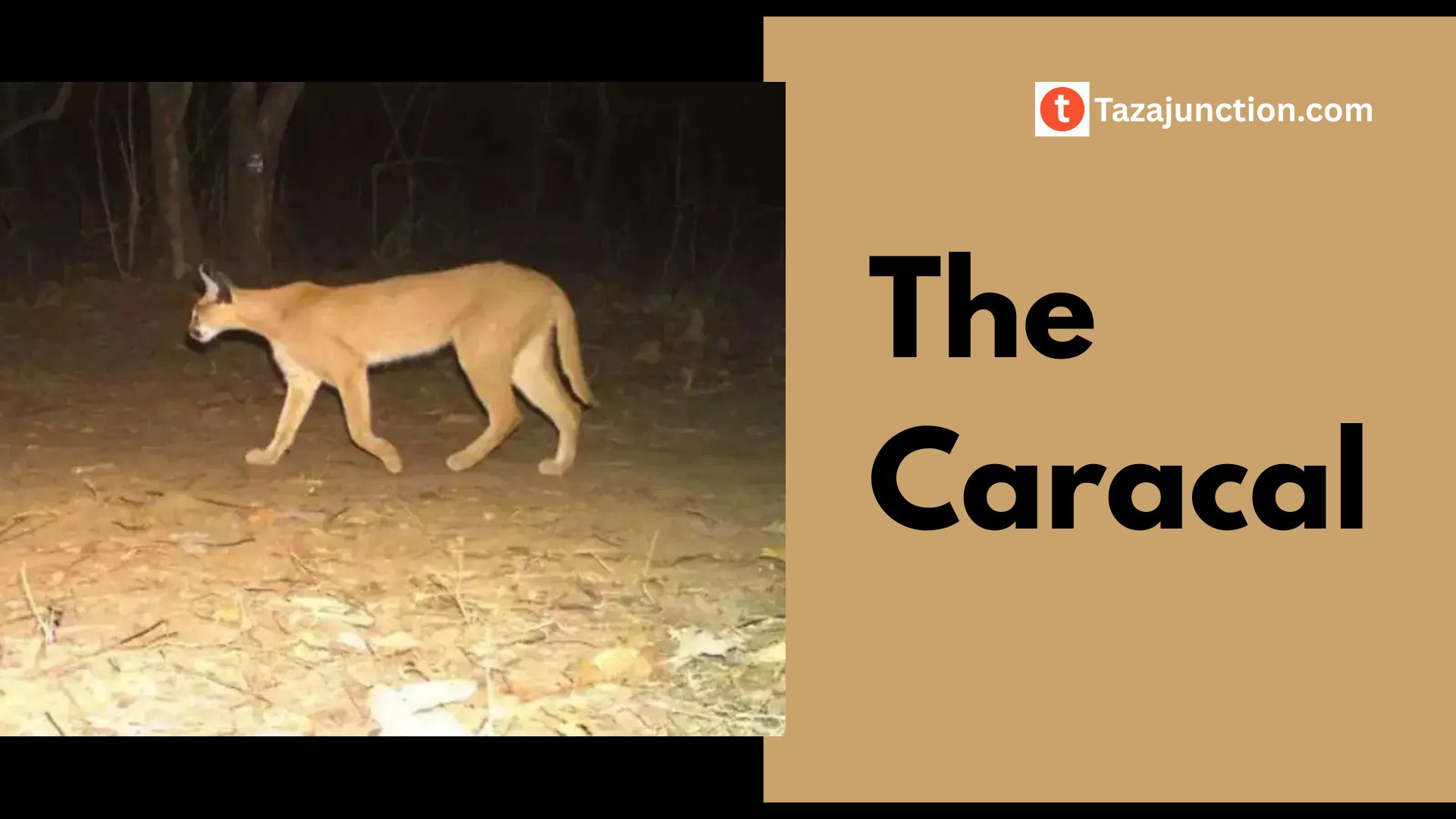

The caracal (Caracal caracal) is a striking feline—its coat a reddish-gold, its body built for stealth and speed, and its face crowned by long black tufts on the ears.

These tufts, which make the carcal instantly recognizable, serve both a sensory and expressive function, helping the cat communicate and detect movement in its environment.

Adapted for dry forests, grasslands, and semi-desert areas, the caracal is known for its extraordinary vertical leaps, often catching birds mid-flight. Solitary and primarily nocturnal, it is a master of camouflage, which, while aiding its survival, also makes it notoriously difficult to study in the wild.

Historically, carcals roamed across parts of Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh, thriving in open habitats alongside blackbucks, hares, and ground-dwelling birds.

But over the last few decades, habitat fragmentation, shrinking prey bases, and human pressures severely diminished their numbers. Until recently, many experts feared that the caracal might have become functionally extinct in India.

The Sightings That Changed Everything

The first crack in the silence came earlier this year when a camera trap in Mukundra Hills, Rajasthan, snapped a single image of a caracal in the wild. The photo sent ripples through India’s conservation community—proof that the species was not gone, merely hiding.

Now, the story deepens with the latest sighting in Madhya Pradesh’s Gandhi Sagar Wildlife Sanctuary, where three distinct images of a caracal were recorded in a single night. This is not just another glimpse—it’s strong evidence that the caracal may be reestablishing itself in parts of its former range.

Forest officials in the region are cautiously optimistic. “This is not a one-off event,” said a senior wildlife officer involved in the camera trap study. “We’re beginning to believe there may be a small, surviving population.”

Why the Caracal Matters

In a country famous for its tigers, leopards, and elephants, smaller carnivores like the carcal are often overshadowed. Yet these lesser-known species play a vital role in the ecosystem.

Caracals are mid-level predators that help regulate populations of small mammals and birds, maintaining a delicate balance in grassland ecosystems. Their presence is also a sign of ecological health: a landscape that can support a secretive predator like the caracal is likely providing for a rich variety of other species.

More broadly, the carcal’s resurgence offers a symbol of resilience. In a time when biodiversity loss often dominates headlines, the return of this graceful hunter is a rare piece of good news.

Fewer Than 50 Left?

Despite these hopeful signs, the situation remains precarious. According to estimates by wildlife experts, fewer than 50 caracals may remain in India today. The exact figure is difficult to pin down, due to their elusive behavior and the lack of focused long-term monitoring.

Conservationists warn that while sightings are encouraging, they should not lead to complacency. “A handful of sightings does not mean the species is safe,” said a field biologist who has studied Indian felids. “It means we have a chance—maybe the last one—to protect this species before it disappears for good.”

Habitat Restoration and Human-Wildlife Balance

One reason behind the recent reappearances may be habitat restoration efforts in areas like Gandhi Sagar and Mukundra Hills. Over the past several years, authorities have focused on afforestation, reducing human encroachment, and protecting prey species in buffer zones. These improvements could be quietly helping caracals and other lesser-known species make a return.

However, conservationists are also quick to highlight the challenges. Shrinking wild habitats, especially dry grasslands, are increasingly being lost to agriculture, development, and neglect. Unlike dense forests—which are often prioritized for tiger conservation—grasslands are poorly understood and rarely protected with the same seriousness.

In addition, human-animal conflict remains a constant threat. Caracals are known to occasionally prey on poultry and small livestock, which could lead to retaliatory killings if local communities are not sensitized and supported.

A New Conservation Priority?

With these sightings gaining attention, there’s growing momentum to include the caracal in future wildlife action plans. Some experts suggest that the government could launch a dedicated Caracal Conservation Program, similar to efforts seen for other species like the Great Indian Bustard and snow leopard.

Madhya Pradesh’s Forest Department has already expressed interest in monitoring caracal populations more closely. Plans are underway to expand camera trap coverage, study potential habitat corridors, and work with local communities to raise awareness.

Further south, officials are evaluating whether reintroduction or breeding programs could support caracal populations, particularly in regions where suitable habitat still exists.

Public Fascination and Global Attention

The caracal’s mysterious reappearance has captured the public imagination. Its elegant form, unusual ears, and acrobatic hunting skills have made it a favorite on social media and in wildlife circles. International conservation bodies are now paying attention as well, seeing in the caracal a broader case study of how overlooked species can be brought back from the edge.

As one wildlife filmmaker commented, “The caracal is a reminder that some of the wildest stories in India aren’t just about the big cats. They’re about the quiet survivors, the creatures that thrive in the margins—if we give them the space.”

Conclusion

India’s caracal is not just a wild cat—it’s a symbol of what can still be saved. From the open grasslands of Gujarat to the rocky outcrops of Madhya Pradesh, its reappearance is a signal that hope is not lost.

But time is short. Without sustained attention, funding, and habitat protection, these recent sightings could become the last flicker of a vanishing species. The challenge now lies not just in celebrating the comeback—but in ensuring that it continues.

If India can protect the caracal—its ghost of the grasslands—it will send a powerful message to the world: that even the rarest lives can still find a way back, when nature is given the chance to heal.